« Return to "Teaching Effectively"

Introduction

Assessment is the process of gathering information about how well a student is achieving specified course and program level learning outcomes. Through assessment, faculty gather information about student performance, provide students with formal or informal feedback, and guide students to improve their learning and skill development. In grading, educators evaluate a students performance on an assessment against specified criterion. Rubrics can be used to provide consistent feedback on an assignment or project. and ensure that the assessments are reliable and valid. Well-designed assessments throughout a program ensure that students are meeting the program learning outcomes by program completion.

Topics of Discussion

Assessing Discussions

Overview

Although discussions take place in the face-to-face learning environment, it can sometimes be challenging to introduce a variety of assessment methods into online teaching and learning spaces. Online discussions are a great way to engage learners, build student community, and promote learning.

Beyond a tool for growing social presence and creating community within a course, online discussions can: measure active participation; gauge comprehension; encourage analysis; focus on evaluation; encourage reflection; and/or prompt synthesis.

How Discussions Work

MyCanvas includes an integrated system for class discussions, which allows educators and learners to start and contribute to discussion topics. Discussions can be created as a graded assignment because of the integration with the MyCanvas gradebook or can simply be used for class participation. Discussions can be organized as focused or threaded discussions:

Focused discussions allow for 2 levels of nesting, the original post and subsequent replies.

Threaded discussions allow for infinite levels of nesting.

Uses of Discussions

Focused Discussions

Threaded Discussions

Questions for Discussion posts can be created by the educator, or the learners can create discussion questions to be answered by their peers.

Functionality within Mohawk's MyCanvas LMS facilitates your creativity when crafting discussions. Options and restrictions allow you to:

From the students' perspective, Discussions in MyCanvas offer robust editing features - students can see the same WYSIWYG editor that they are used to using in Word and can enhance their contributions with images, hyperlinks, embedded videos, etc.

In-Person/Synchronous Discussions

Discussions can also take place in in-person or synchronous online classes. These discussions can be completed in small groups or breakout rooms, where individuals from each group are selected to report the discussion findings of their smaller group. The debriefing method is important to ensure that students are summarizing the most important aspects of their discussion. Some debriefing techniques include: verbally, newsprint/flipchart, whiteboard, screen sharing, etc. Large group discussions can also be used with some classes, but the educator should be mindful of ensuring that the group stays on task.

Assessing Discussions

Learners may have distinct ideas of what a quality discussion is, so it is important to clearly outline course expectations. You can attach a score to an individual thread, multiple contributions by a learner or associate a rubric with the topic. A discussion rubric can be used to ensure that all learners are on the same page and build learner accountability. Another method of assessing discussion participation is having the learner keep track of what they have learned in the class discussions, both in person and virtually, and submit a reflection on their learning. Either score can link directly to Grades.

Assessing in-person discussions can be challenging, especially with larger groups. In this case, assessment can be based on participation, contribution, peer grading, etc. Another way to assess participation in class discussions is to have learners submit a reflection on the discussion topic and the ideas presented in class.

Use at Mohawk

Discussions are a widely used assessment method at Mohawk College. Many educators use them in all modalities of learning; Hybrid, Online Asynchronous, Online Synchronous, in-person and HyFlex. When used appropriately discussions can be an effective assessment tool. Consider adding variety in your discussions, especially those posted in the LMS. For example:

Consistent use of the tool is wonderful for learner experience of online learning, but varying how the tool is used is equally important for engagement and ensuring that the task does not become monotonous.

Additional Resources

Brank, E., & Wylie, L. (2013). Let's discuss: Teaching students about discussions. Journal Of The Scholarship Of Teaching And Learning, 13(3), 23-32

Not specifically detailing online discussion, but an interesting article exploring how to approach the importance of discussions with students. Connects the engagement with discussions to deeper success in the course. The list of references are also a sound springboard to more information.

Lai, K. (2012). Assessing participation skills: online discussions with peers. Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Education, 37(8), 933-947. doi:10.1080/02602938.2011.590878

A comprehensive analysis of a specific example for an online discussion forum. The highlight on students' critical thinking skills and how to assess and evaluate them will be of particular interest. The author provides exemplars of the different levels of performance as well as various marking guidelines from checklist to rubric.

Assessment

Assessment is the process of gathering information about how well a student is achieving specific outcomes. Through assessment, faculty gather information about student performance, provide students with formal or informal feedback, and guide students to improve their learning.

Evaluation is an assessment of learning - where students demonstrate their learning through a performance task that faculty can use as evidence of student achievement. This evidence is how we determine whether a student has met the learning outcomes for a lesson, unit, course, or program.

Feedback and Assessment

Assessments are a critical part of every course. They are the way we measure whether students have met the course learning outcomes and should earn the credit.

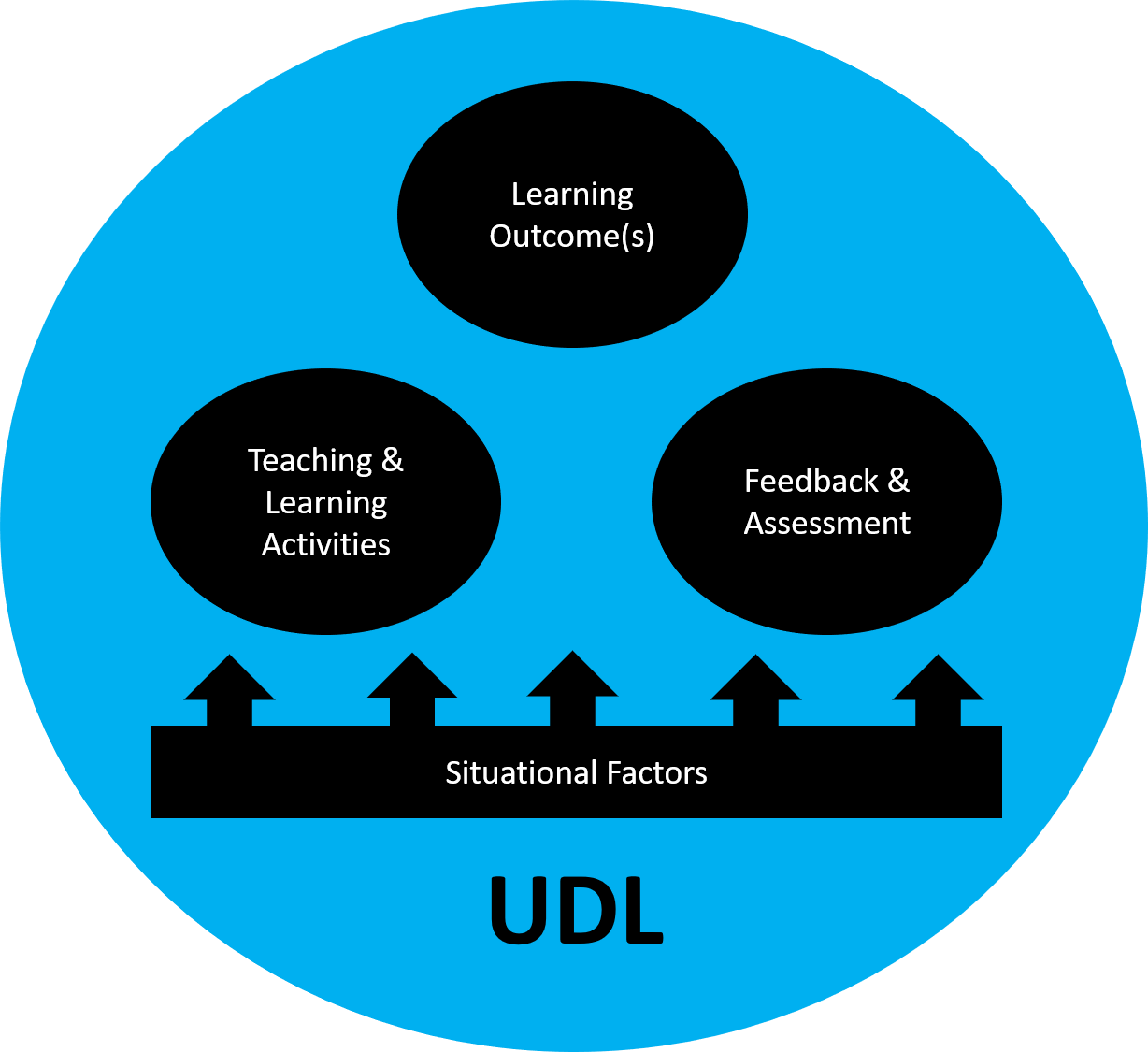

Any course assessment must align with the learning outcomes. After all, assessments should measure whether learners demonstrated they have met the course learning outcomes. The graphic below demonstrates how Learning Outcomes, Teaching & Learning Activities, and Feedback & Assessment are connected.

You'll also note in the graphic that Universal Design for Learning (UDL) underpins all elements in course design. Considering the diverse learners in a course, feedback and assessment opportunities should be carefully designed to reduce barriers, while allowing students to demonstrate their level of achievement of the course learning outcomes.

Applying UDL to assessments and feedback can be as simple as allowing students to choose a project topic from a list or allowing students a choice in the way they will demonstrate their learning, as long as the choices align with the course learning outcomes.

Use at Mohawk

Mohawk's Student Assessment Policy explains that faculty develop assessments based on the outcomes students will achieve as part of their course. Program areas work together to determine how the assessments from each course contribute to the overall learning outcomes for the program.

These assessments should provide an authentic representation of students' abilities, reflect the outcomes (VLOs, EESs, and CLOs) and strike a balance between providing a realistic student workload and providing multiple opportunities to demonstrate learning and receive feedback.

Diagnostic, Formative, and Summative Assessment

As mentioned earlier, assessments are opportunities to provide students with feedback on their progress within a course. They allow students to understand their development of the Course Learning Outcomes (CLOs), Vocational Learning Outcomes (VLOs) and the Essential Employability Skills (EESs). Assessments are not only used for educators to assess students, but they provide students with the opportunity to evaluate their personal learning journey. There are three types of assessment; Diagnostic, Formative and Summative.

Diagnostic

Diagnostic assessment is used at the beginning of a course, instructional unit or topic to gauge what learners already know about the content. Diagnostic assessment also assists the educator with the direction to take for a lesson.

"If students know that the purpose is to diagnose strengths and weaknesses and provide meaningful feedback instead of assigning a grade, they can take risks to reveal weaknesses." (Aitken, N, 2011, p. 182) As such, diagnostic assessments are used FOR learning.

Examples of Diagnostic Assessment

Characteristics of Diagnostic Assessments

Formative

Formative assessment has been defined as "activities undertaken by teachers and by their students in assessing themselves - that provide information to be used as feedback to modify teaching and learning activities" (Black & Wiliam, 2010, p. 82).

Formative assessment is evaluation AS the learning occurs. It is used to gauge student learning, as such formative assessments are used FOR learning.

Examples of Formative Assessments

Characteristics of Formative Assessments

Summative

"Summative assessments should not only give students the chance to demonstrate their conceptual understanding, but also give students the opportunity to think critically as they apply their understanding under novel conditions to solve new problems" (Dixson, & Worrell, F. C, 2016, p. 156)

Summative assessment is evaluation OF learning. It is used to determine what has been learned at the end of an instructional unit or topic.

Examples of Summative Assessments

Characteristics of Summative Assessments

Summary of Diagnostic, Formative, and Summative Assessment Characteristics

Diagnostic, Formative and Summative assessments "are complementary and the differences between them are often in the way these assessments are used" (Dixson, & Worrell, 2016, p. 153). At Mohawk College, we recommend a blend of the three to provide learners with a more balanced approach.

| Characteristic | Diagnostic | Formative | Summative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose |

|

|

|

| Formality | Informal | Usually informal | Usually formal |

| Timing | At the beginning | Ongoing | Cumulative |

| Questions to ask |

|

|

|

Deciding Which Assessments to Use

Faculty have a wide array of assessments to choose from for their courses, including written assignments, group projects, presentations, case studies, lab activities, simulations, real world projects, quizzes, exams, and student-driven projects. To decide which assessment fits best, consider:

From: Drake, S. (2007). Creating Standards-Based Integrated Curriculum: Aligning curriculum, content, assessment, and instruction. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin - page 8.

These questions will help you to choose an assessment task that is aligned with the outcomes learners will meet in a course.

Check out some of these examples from courses at Mohawk:

As often as possible, you should select an authentic assessment task. That is, the task students perform in the course should:

Additional Resources

References

Aitken, N. (2011). Student Voice in Fair Assessment Practice. In: Webber, C., Lupart, J. (eds) Leading Student Assessment. Studies in Educational Leadership, vol 15. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi-org.uproxy.library.dc-uoit.ca/10.1007/978-94-007-1727-5_9

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2010). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(1), 81-90. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171009200119

Dixson, & Worrell, F. C. (2016). Formative and Summative Assessment in the Classroom. Theory into Practice, 55(2), 153-159. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1148989

Queen's University. (n.d.). Diagnostic assessment. Queen's University Canada. https://www.queensu.ca/teachingandlearning/modules/assessments/10_s2_02…

Authentic Assessment

Defining Authentic Assessment

Authentic Assessment is important in higher education because it can help prepare students with the skills and tasks they will need in the workplace. As Authentic Assessments involved real-world tasks that are relevant to students.

Traditional Assessment vs Authentic Assessment

What is the difference between traditional assessments and authentic assessment?

Traditional

Authentic

"Authentic assessment drives the curriculum" (Meuller, 2018) versus traditional assessment where the curriculum drives the curriculum. In Traditional Assessment the assessment is completed to ensure learners have gained the required skills and knowledge. In Authentic Assessment the goal is to ensure that when learners graduate, they are able to perform in the real world, therefore Authentic Assessment tasks learners with real-world examples. In essence, assessments are created to ensure students can demonstrate mastery, then the curriculum is created to support the assessment. This is also called backwards design.

Authentic assessments are direct measures. We want students to be able to use their acquired knowledge and skills in the real world, after they graduate. Authentic Assessment can capture constructive nature of learning, by having them demonstrate capability instead of just answering questions about capability. The same task used to evaluate learning, is also used as a vehicle for the learning. Authentic assessment allows for multiple paths to the same result, other words students will demonstrate their learning of a concept in different ways.

Note: Authentic Assessment complements traditional assessment, a combination of both can be used to ensure students have achieved the learning outcomes of a course.

Benefits

Four Steps to Creating an Authentic Assessment

"Authentic tasks do not have to be large, complex projects. Most mental behaviors are small, brief "tasks" such as deciding between two choices, or interpreting a political cartoon, or finding a relationship between two or more concepts. Thus, many authentic tasks we give our students can and should be small and brief, whether they are for practicing some skill or assessing students on it. (Mueller, 2018)"

Example

Learning Objective: Write original code to demonstrate the use of a programming concept.

Task: Make a captioned video that uses code you've written to explain a programming concept with a real-world application. Post the video link in a MyCanvas discussion. Review and provide feedback on two peers' videos.

What the researchers say

Jon Mueller

"A form of assessment in which students are asked to perform real-world tasks that demonstrate meaningful application of essential knowledge and skills" (Mueller, 2018)

Grant Wiggins

"...Engaging and worthy problems or questions of importance, in which students must use knowledge to fashion performances effectively and creatively. The tasks are either replicas of or analogous to the kinds of problems faced by adult citizens and consumers or professionals in the field." (Wiggins, 1993, p. 229).

Richard Stiggins

"Performance assessments call upon the examinee to demonstrate specific skills and competencies, that is, to apply the skills and knowledge they have mastered." (Stiggins, 1987, p. 34).

Additional Resources

UDL and Assessment

References

Mueller, J. (2018). What is authentic assessment? (Authentic assessment toolbox). https://jonfmueller.com/toolbox/

Online Network of Educators. (2020, June 17). Authentic assessment guide. https://onlinenetworkofeducators.org/pocket-pd-guides/authentic-assessm…

Stiggins, R. J. (1987). The design and development of performance assessments. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 6, 33-42.

Wiggins, G. P. (1993). Assessing student performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Designing Multiple Choice and True/False Questions

When designing and creating quality multiple choice and true/false questions, educators need to be purposeful in all aspects of questions and answer design. Please use the guidelines below to assist in designing quality multiple choice and true/false questions:

- Use clear and concise language to avoid any ambiguity or confusion. Make sure the questions are easily understandable and do not contain unnecessary jargon or complex sentence structures.

- Ensure that the questions are directly related to the course learning materials and cover the key concepts. Avoid including irrelevant or trivial information that could distract or mislead the students.

- When possible, frame the questions within authentic scenarios or contexts that reflect real-world situations. This helps students see the practical applications of the concepts they are learning and enhances engagement.

- The questions should align closely with the course learning outcomes. Each question should assess specific knowledge or skills that students are expected to acquire within the modules.

- For multiple choice questions, provide conceivable distractors that closely resemble the correct answer. This ensures that students must understand the content fully to select the correct option, making the question more challenging.

- Randomize the order of the answer choices to avoid any unintentional patterns or biases. This ensures that students cannot rely solely on the position of the correct answer and encourages them to carefully evaluate each option. It is strongly recommended, when possible, to randomize question order as well.

- Clearly state the instructions at the beginning of the assessment to guide students/learners on how to respond to the multiple choice and/or true/false questions. Specify whether the question is multiple choice (single correct answer) or multiple answer (multiple correct options) for multiple choice questions.

- Include questions that assess different cognitive levels, such as recall, understanding, application, analysis, and synthesis. This allows students to demonstrate a deeper understanding of the content and promotes critical thinking skills.

- Apply universal design principles by considering the needs of diverse learners. Ensure that the questions are accessible to students with disabilities and provide alternative formats if necessary, such as providing a text-to-speech option for visually impaired students.

- If the question is a multiple answer question, ensure to clearly specify all learners should select all answers that apply to the question. For example, add "select all the apply" to the question.

Example Questions taken from Yale University Centre for Teaching & Learning.

In the following examples of effective and ineffective MC questions, students explore potential energy, or the energy that is stored by an object.

#1. Good Stem, Poor Distractors

Potential energy is:

a) the energy of motion of an object.

b) not the energy stored by an object.

c) the energy stored by an object.

d) not the energy of motion of an object.

In this question the good stem is clear, brief, and presents the central idea of the question through positive construction. However, the distractors are confusing: b) and d) are written in negative constructions that force students to reinterpret the stem, while c) and d) have overlapping, inconsistent content that confuses and tests reading comprehension over content recall. Finally, choices do not move logically by grouping content, failing to visualize and test larger concepts for students.

#2. Poor Stem, Good Distractors

Potential energy is not the energy:

a) of motion of a particular object.

b) stored by a particular object.

c) relative to the position of another object.

d) capable of being converted to kinetic energy.

In this question the poor stem contains the word "not," which fails to identify what potential energy is, and tests grammar over student understanding. However, the good distractors are written clearly, cover unique content, and follow a logical and consistent grammatical pattern.

#3. Good Stem, Good Distractors

Potential energy is:

a) the energy of motion of an object.

b) the energy stored by an object.

c) the energy emitted by an object.

In this example both the stem and the distractors are written well, remain consistent, and test a clear idea.

Additional Resources

The University of Waterloo provides additional information on designing Multiple Choice questions.

References

Yale Center for Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Designing quality multiple choice questions. Retrieved from: https://ctl.yale.edu/MultipleChoiceQuestions

Learner Reflection

In 1933, American psychologist and educational reformer John Dewey noted that we do not learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience.

Having learners participate in reflection activities solidifies the connection between the experience and what they learned. If a student does not reflect on an experience, it is difficult to assess what they have learned. It helps develop critical thinking skills by allowing learners to examine their strengths and explore areas for improvement in their future learning.

Reflection is a key component of experiential learning. According to Ontario's Ministry of Colleges and Universities' Guiding Principles for Experiential Learning, all Experiential Learning must include student self-assessment - in other words, a graded reflection.

Adding reflection to student assessment

Reflective learning can either be added to existing assessments or be stand-alone assignments. It can include larger assignments such as reflective journals, portfolios, goal setting, and more.

Reflection can be done using a reflective framework, such as the Reflective Cycle (Gibbs, 1988) that has six stages:

- Description: What happened?

- Feelings: What were you thinking and feeling?

- Evaluation: What was good and bad about the experience?

- Analysis: What sense can you make of the situation?

- Conclusion: What else could you have done?

- Action Plan: What would you do next time?

Implementing Group Work in the Classroom

Adapted from University of Waterloo.

Group work can be an effective method to motivate students, encourage active learning, and develop key critical-thinking, communication, and decision-making skills. But without careful planning and facilitation, group work can frustrate students and instructors, and feel like a waste of time. Use these suggestions to help implement group work successfully in your classroom.

Preparing for Group Work

Designing the Group Activity

Introducing the Group Activity

Monitoring the Group Task

Ending the Group Task

Additional Resources

Teaching Tips

Other Resources

References

Brookfield, S.D., & Preskill, S. (1999). Discussion as a Way of Teaching: Tools and Techniques for Democratic Classrooms. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Gross Davis, B. (1993). Tools for Teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Jaques, D. (2000). Learning in Groups: A Handbook for Improving Group Work, 3rd ed. London: Kogan Page.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (2014). Cooperative learning: Improving university instruction by basing practice on validated theory. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 25(3&4), 85-118.

Race, P. (2000). 500 Tips on Group Learning. London: Kogan Page.

Roberson, B., & Franchini, B. (2014). Effective task design for the TBL classroom. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 25(3&4), 275-302.

Rubrics

Defining Rubrics

A rubric is an assessment tool that explains marking criteria for course assessments. They divide assessments "into component parts" and describe the expected level of performance for each part (Stevens & Levi, 2013). Rubrics can be used for a variety of assessment types, such as essays, projects, presentations, discussions, and reflections.

One can define the term rubric as:

Relevant User-friendly Benchmarks Reinforcing Instruction and Cultivating Success

This concise definition was crafted as an acronym but it provides a concrete description of the purpose of a rubric.

A rubric is a table that provides performance criterion (left hand column) and levels of achievement (top row) to better communicate assignment expectations with learners for assessment and evaluation.

"At its most basic, a rubric is a scoring tool that lays out the specific expectations for an assignment" (Stevens & Levi, 2013, p 3).

How Rubrics Work

A rubric should accompany each assessment in a course. Rubrics can take on many forms; however, usually there are four levels of achievement (4, 3, 2, 1) that correspond to four grades A, B, C and D starting from the highest to the lowest level, reading left to right in the table. In some cases, there may only be 3 levels of achievement.

Criterion outline what part of the assessment the levels of achievement are referring to. For example, you may want to focus on Grammar and Spelling in one criterion and content development in another.

For each criterion, the educator crafts a description for each level of achievement, from acceptable to unacceptable (or level 4 to level 1). For example, each cell or box of the matrix has a unique entry that explains what is expected in order to achieve the specified level (i.e. level 4, 3, 2, or 1).

The educator uses the rubric to assess and evaluate learner work. Rather than having to write lengthy feedback/comments, the rubric speaks to areas of strength and weakness. A learner can easily identify assessment expectations in order to be successful. Overall, learners receive a more comprehensive assessment of their contribution/learning and recognize the alignment of the assessment to important outcomes, skills, and abilities.

Benefits

Faculty Benefits:

Student benefits:

Common Missteps

Educators tend to over-conceptualize their descriptions, causing difficulty for the learner to connect their levels of performance to learning outcomes and identify areas for improvement. Among the different levels of achievement, the following qualifiers are used in order to ensure that the outcome is clear:

Use of the terms above makes progression along the continuum easier to discern for both educators and learners.

Use at Mohawk

Rubric use is encouraged at Mohawk College and the Centre for Teaching & Learning Innovation is available to assist with the creation of your rubrics. A Curriculum and Program Quality Consolation (CPQC) can assist with the creation/wording of rubrics.

In addition, MyCanvas has a built-in Rubrics tool that allows educators to build digital rubrics directly into the Learning Management System. Any rubrics created in MyCanvas can be associated with assessments making online evaluation and feedback seamless. An Instructional Designer (ID) can support faculty with implementing rubrics in the LMS.

References

Queens University. (n.d.). Rubrics and marking schemes. Queen's University Canada. https://www.queensu.ca/teachingandlearning/modules/assessments/34_s4_04…

Stevens, Levi, A., & Walvoord, B. E. (2013). Introduction to rubrics: an assessment tool to save grading time, convey effective feedback, and promote student learning (Second edition.). Stylus.

Western University. (n.d.). Grading with rubrics. Centre for Teaching and Learning - Western University. https://teaching.uwo.ca/teaching/assessing/grading-rubrics.html

Still have Questions?

Reach out to CTLI Support Today!